There is a story of overarching significance for every one of us and for society as a whole. It is the story of life on Earth and the human place in nature [1]. Yet this story is known and understood by only a minority of the human population. If it were understood by the majority, the prospects for humanity would be much brighter. We refer to this story as the Bionarrative.

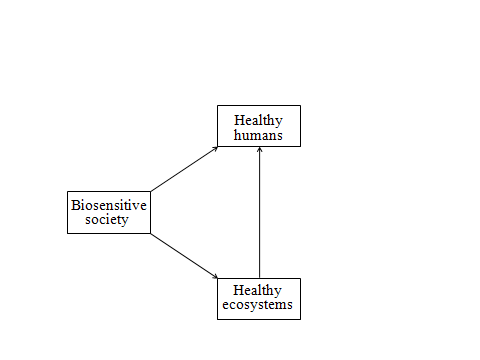

The Bionarrative conveys a sense of perspective crucial for understanding the human situation on Earth today. It reminds us that we are living beings, products of several billion years of biological evolution, and totally dependent on the processes of life, within us and around us, for our wellbeing and survival. Keeping these processes healthy must be our top priority, because everything else depends on them.

More specifically, the Bionarrative tells us that:

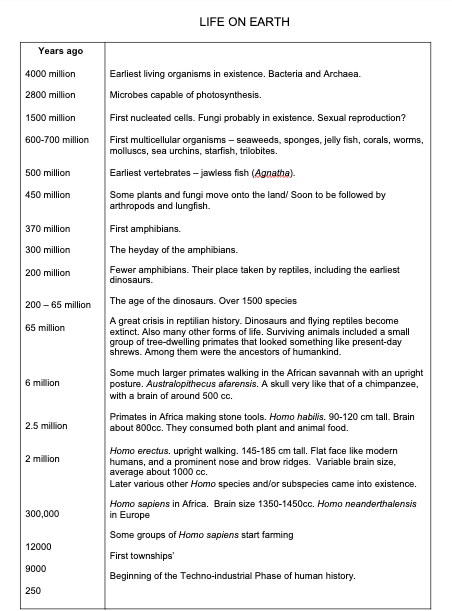

Our planet is about 4600 million years old. The sun provides it with a constant supply of energy, in the form of visible light, and ultraviolet and infrared radiation.

The earliest living organisms on Earth came into existence over 4000 million years ago. They were single-celled microbes, and they were the most complex form of life for over 1000 million years. There were, and still are, two distinct groups of such micro-organisms, with different biochemical characteristics. They are classified as Bacteria and Archaea. The Archaea include microbes that live and multiply under extreme conditions, such as very high temperatures and salinity.

It is believed that the main sources of energy for these early single-celled organisms were energy-containing chemical compounds that had formed through the action of ultraviolet radiation from the sun and electrical discharges in storms. But the amount of energy from such sources was strictly limited, and there was certainly not enough of it to sustain life on the scale that exists today. Microbes capable of photosynthesis came into existence around 2800 million years ago.

Microbes capable of photosynthesis came into existence around 2800 million years ago. Photosynthesis is the process by which light energy is captured from sunlight and converted complex energy-containing molecules in the organism. All animal and plant life on Earth today depends on photosynthesis in green plants.

Like bacteria today, the earliest single-celled organisms did not possess nuclei. The first nucleated cells appeared about 1,500 million years ago, and it seems that a great evolutionary diversification began to take place among living forms around this time, suggesting that a form of sexual reproduction was by then in existence. Previously, all reproduction had been asexual, involving the simple division of one cell into two. In sexual reproduction a new individual comes into existence through the union of two cells, the male and female gametes, each bringing its complement of genetic material from one of the parent organisms.

Fungi may have been in existence 1.5 billion years ago, and they were much in evidence 600 million years ago. Like animals, they get their energy and carbon from other organisms.

The first multicellular organisms came into being 600-700 million years ago. They included seaweeds, sponges, jelly fish, corals, worms, molluscs, sea urchins, starfish, lamp shells, and trilobites.

Since that time biological evolution has resulted in the coming and going of myriads of life forms, leading to the rich network of interacting and interdependent organisms that exist in our world today.

The earliest vertebrates were jawless fish (Agnatha) that lived around 500 million years ago.

The plants of the oceans have changed little since that time. In contrast, spectacular evolutionary changes took place among animals in the aquatic environment. By 200 million years ago the trilobites had entirely disappeared and were replaced by a new group of molluscs known as ammonites. At one time there were over twenty different families of ammonites, and some of them had a diameter of at least a metre. But the ammonites were also extinct by 60 million years ago.

Meanwhile there was remarkable diversification taking place among the bony fishes, leading eventually to the immense variety of fish species found in ponds, streams, rivers, lakes and oceans today.

By 450 million years ago, and possibly before this time, some plants and fungi were moving onto the land masses of the planet, soon to be followed by various kinds of arthropods. Vertebrates, in the form of lungfish, were venturing onto land 400 million years ago.later.

The early land plants evolved from a group of green algae. They included mosses, ferns and gymnosperms, like cycads, gingkos and conifers, followed much later by the angiosperms (flowering plants).

The heyday of the amphibians was around 300 million years ago. By 200 million years ago, their numbers had declined dramatically, and their place had been taken by reptiles, including the earliest dinosaurs. Birds and mammals evolved directly from the reptiles, which in turn had evolved from the amphibians.

The reptiles included the dinosaurs, which thrived from 200 to 65 million years ago There were many different kinds of dinosaur, adapted to different kinds of habitat. Several aquatic groups evolved, some of which looked very much like fish, although they did not have gills, and they breathed air through a respiratory tract. There were also various forms of flying reptiles, with wings consisting of leathery membranes, supported and extended by very elongated fingers. Some of them had a wingspan of over 7 metres.

The earliest mammals came into existence about 200 million years ago, at about the same time as the dinosaurs were emerging, and there were animals very like modern echidnas living around 150 million years ago. However, mammals remained a rather insignificant group during this period of reptile dominance.

The first true flowering plants emerged about 160 million years ago, and since that time they have undergone spectacular diversification. They are now the dominant division of plants and are made up of two main groups, the monocotyledons and dicotyledons. In the monocotyledons, which include grasses, lilies, irises and crocuses, the seedling has a single leaf and the stems do not thicken. The seedlings of dicotyledons have two leaves and the stems become thicker as the plant matures.

Around 65 million years ago a great crisis occurred in reptilian history and many forms became extinct, including all the dinosaurs and flying reptiles and most of the large marine reptiles. This wave of extinctions is thought to have been caused by the impact of a massive comet, or asteroid, landing on the Earth. Many other forms of life disappeared at this time, including various microscopic foraminifera in the oceans and many aquatic animals,

including the ammonites. Placental mammals, birds, lizards, snakes, turtles, crocodiles, fishes and plants were relatively unaffected.

After about 60 million years ago there was widespread evolutionary diversification among birds and mammals.

Estimates of the number of different species alive today are very variable. The most widely cited estimate is 8.7 million, although some authorities believe the number is much greater than this.

Some common features shared by many animal species go back a very long way in evolution. The mouth and anus were in existence 600 million years ago. Among vertebrates, two eyes, two ears, a heart and a stomach go back at least 550 million years; and four five-toed (or fingered) limbs go back to the earliest amphibians, around 400 million years ago.

HOMO SAPIENS APPEARS ON THE SCENE

During the last part of the dinosaur era around 65 million years ago, there existed on Earth a small group of tree-dwelling primates that looked something like present-day shrews. Among them were the ancestors of humankind.

Five or six million years ago there were some much larger primates walking in the African savannah with an upright posture. One particularly well-preserved fossil is that of a young female found in Ethiopia and dated about 3 million years ago. She is known informally as Lucy, and the species she belonged to has been called Australopithecus afarensis. She had a skull very like that of a chimpanzee, with a brain of around 500 cc.

Two and a half million years ago there were primates in Africa making stone tools. One species, called Homo habilis, was 90-120 cm tall, and it had a brain with a volume of about 800cc, which is about 300cc larger than the brain of a chimpanzee. These animals consumed both plant and animal food. Another rather similar species called Homo rudolfensis existed at about the same time.

After that, several different human species came into being, including Homo erectus. This was an upright walking species, 145-185 cm tall. It had a flat face like modern humans, and a prominent nose and brow ridges, with a brain size that ranged from 546 cc to 1251 cc, with an average of about 1000 cc. It existed in Africa 2 million years ago, and then spread into and across Eurasia. The latest known population lived in Java around 110 000 years ago.

The earliest ‘modern humans’, Homo sapiens, were living in parts of Africa around 300,000 years ago. They were tall people, with rounded skulls and steep foreheads, and their average cranial capacity was about 1,400cc. They had well developed chins, and their brow ridges were only moderately developed, and were not continuous from side to side. If we could bring some of them back to life, dress them in modern clothing and set them loose on a city street, they would be indistinguishable from some of the better specimens of modern humanity.

From about 200,000 years ago, and during most of the first part of the fourth, or Würm, glaciation, western Europe was occupied by a distinctive form of humanity classified as Homo neanderthalensis. These people were of stocky build and most of the men were a little over 152 cm tall, and the women a little shorter. Their skulls were flattish on top and noticeably rounded at the back, and they had a pronounced brow ridge reminiscent of Homo erectus. They had massive musculature and jaws, and the brains of adults ranged from 1,450 cc to 1,650 cc in volume. They were well acquainted with the use of fire, they hunted big game and they dressed in animal skins. They used paints to decorate their bodies and sometimes they buried their dead. The Neanderthals were displaced in Europe by Homo sapiens around 40,000 years ago.

Apart from the Neanderthals and Homo sapiens, at least three other kinds of humans are known to have been living outside Africa at about that time. Homo denisova lived across Asia and Homo longi (Dragon man) was in China. Although they are classified a distinct species, both the Neandethals and the Denisovans interbred with Homo sapiens. Dwarf hominids, called Homo floresiensis, existed on the island of Flores in Indonesia until about 50,000 years ago. They looked rather like Homo habilis.

Homo sapiens continued to live as hunter-gatherers until about 12,000 years ago, when some of them started farming. The human population is thought to have been about 5 million at that time.

Human culture

Homo sapiens possesses an attribute now unique in the animal kingdom – the ability to invent, memorise and communicate with a symbolic spoken language. This aptitude for language led to the accumulation of shared worldviews, knowledge, beliefs, attitudes and technological knowhow in human groups. That is, it led to human culture.

Human culture has recently become a new and powerful force in nature. Cultural assumptions, values and arrangements, through their influence on human behaviour, have major impacts on other living organisms and on ecosystems. There is thus constant interplay between human culture and biological systems.

Culture has led to activities that have been to the benefit of humans, referred to as cultural adaptations, and to activities that have been greatly to their disadvantage, referred to as cultural maladaptations.

The control and use of fire for cooking and other purposes was one of the turning points in cultural evolution. It predates Homo sapiens. Fire was probably in use by Homo erectus a million years ago.

The history of Homo sapiens has consisted of four quite distinct ecological phases:

Phase 1 – The hunter-gatherer phase

This was by far the longest of the four ecological phases, lasting at least 300 000 years.

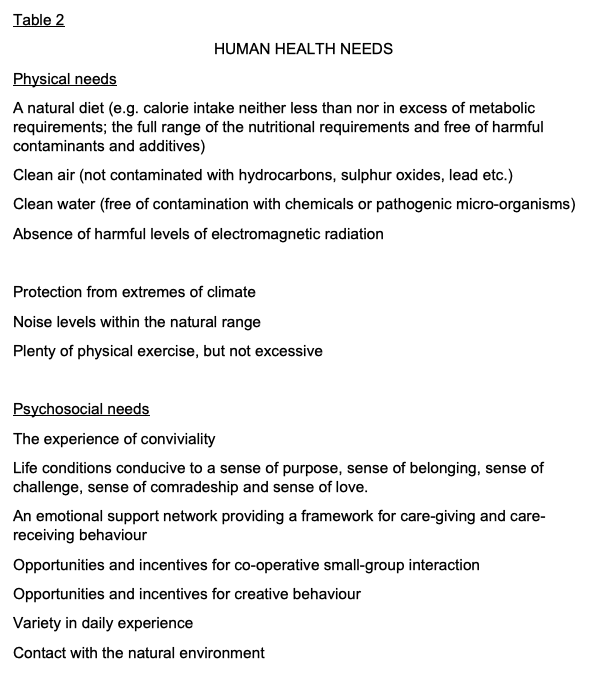

As in the case of all other animal species living in their natural habitats, for most of the time most members of hunter-gatherer bands are likely to have been in a state of good health. Indeed, they had to be in order to survive and successfully reproduce under the demanding conditions of their lifestyles and environment. Because of the relatively low population density, people would not have suffered from such respiratory and enteric virus infections as common colds, covid-19, influenza, gastric flu, measles, smallpox and German measles. Nor are they likely to have experienced bacterial infections like cholera and plague. However, infection with bacteria following injury would have been a constant hazard.

Ecologically the most important culturally inspired activities in this phase were the deliberate use of fire and the manufacture and use of tools and weapons.

Phase 2 – The early farming phase

Homo sapiens had probably been in existence for around 300,000 years before farming began. It started in several parts of the world around 10,000 to 12,000 years ago. This development marked a turning point in cultural evolution. It was a precondition for all the spectacular developments in human history that have occurred since that time.

Phase 3 – The early urban phase

This phase began around 9000 years ago, when fairly large clusters of people, sometimes consisting of several thousand individuals, began to aggregate together in townships. Many of these people played little or no part in the gathering or production of food. Occupational specialisation became the hallmark of urban societies.

Although the new conditions offered protection from many of the hazards of the hunter-gatherer lifestyle, malnutrition and infectious disease became much more important as causes of ill health and death.

Phase 4 – The techno-industrial phase

This phase was ushered in by the techno-industrial revolution, which began about 250 years ago. It has been associated with profound changes in the ecological relationships between human populations and the rest of the biosphere.

Ecological Phase 4 has recently come to be referred to as the Anthropocene, and because of the popularity of this term, it will be used in the rest of this document.

The Anthropocene has seen an astounding profusion of technological innovations – from steam engines and motor vehicles to intercontinental rockets and spacecraft – and from electric lights, telephones and radios to thermonuclear bombs, computers, smartphones and the Internet.

There has been a massive intensification of use of resources and energy and discharge of wastes by humankind.

Cultural maladaptations in the Anthropocene are on a scale and of a kind that threaten the whole of humankind, as well as countless other species.

Anthropocene perspectives

Population

There are now about 1,600 times as many people alive as there were when farming began. Nearly 90 per cent of this increase has occurred in ecological Phase 4. The global population is at present increasing at the rate of 1.4 million per week.

Greenhouse gases

If it were not for certain gases occurring naturally in the atmosphere, the world’s average temperature would be 33°C colder than it is. The average temperature would be around minus 19°C instead of plus 14°C. This is because these gases trap some of the infrared radiation that escapes from the Earth’s surface. This blanketing effect results in the lower layers of the atmosphere being warmer, and the upper layers colder, than if these gases were not there. This phenomenon is known as the natural greenhouse effect.

Water vapour is responsible for about 80% of the natural greenhouse effect. The remainder is due to carbon dioxide, methane, and a few other minor gases. Carbon dioxide (CO2) is responsible for about 15% of the natural greenhouse effect. Were it not for the CO2 in the atmosphere, the Earth’s average temperature would be 5°C cooler than it is.

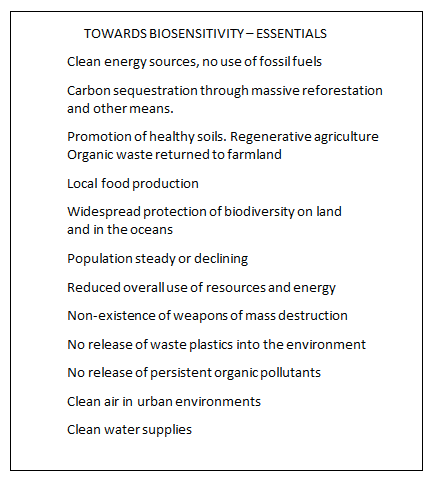

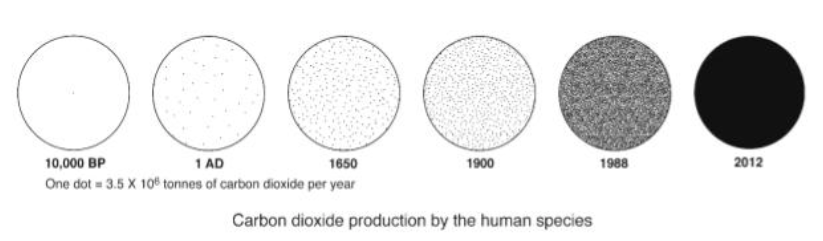

For the first 300,000 years of the history of Homo sapiens, the mixture of these greenhouse gases was relatively constant. During the past two hundred years there has been an increase in the CO2 concentration in the atmosphere – from 292 parts per million to the current 420 parts per million. This increase in atmospheric CO2 is mainly the result of two sets of human activities: deforestation, and the combustion of fossil fuels.

The amount of carbon dioxide emitted by the human population today is around 10,000 times greater than it was when farming began some 450 generations ago, and 90% of this increase has occurred over the past 100 years.

The increase in atmospheric carbon dioxide is responsible for 53% of the current global warming. Humankind has also caused the release of several other greenhouse gases, most notably methane, halogenated compounds, tropospheric ozone and nitrous oxide.

The methane (CH4) is generated by activities like production of livestock, especially ruminants, sewage treatment, distribution of natural gas and oil, coal mining and fossil fuel use. It is responsible for 15% of current global warming. Halogenated compounds, like CFCs, HFCs and PFCs, are used in various industrial processes. They contribute 11% of current global warming. Tropospheric ozone (O3) is given off during the combustion of fossil fuels. It contributes 11% of current global warming. Nitrous oxide (N2O) comes mainly from use of fertilisers and use of fossil fuels. It contributes about 11% of current global warming.

As a consequence of this anthropogenic increase in greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, the Earth’s average surface temperature has already increased by about 1°C. This is referred to as the enhanced greenhouse effect.

Sea levels are rising, and there is an increasing frequency of extreme weather events worldwide, such as powerful storms, typhoons, droughts and heatwaves. If governments do not take strong action in the immediate future, the consequences for humanity will be very serious indeed

Deforestation

Deforestation of tropical forest is occurring at an ever-increasing rate – mainly to make way for pastures for beef cattle and oil palm plantations. Only about 6 million square kilometres remain of the original 16 million sq. km. of tropical rainforest that formerly existed on Earth. Over 30 million acres of forests are lost every year due to deforestation.

Deforestation is an important influence in global warming. It has been estimated that more than 1.5 billion tons of carbon dioxide are released to the atmosphere every year due to deforestation.

Waste production and pollutants

Plastics have been introduced for manufacturing a very wide range of objects. About 9 million tonnes of plastic waste are discharged into the sea every year, and the amount has been predicted to double in 11 years. Environmental pollution with discarded plastics is causing a dramatic decline in populations of many seabirds. 5000 – 15000 turtles become entangled in discarded fishing gear every year. According to one prediction, by the year 2050 there will be more plastic in the oceans than fish.

The release into the atmosphere of chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) and halons – gases formerly found in aerosol spray cans and refrigerants, has resulted in some thinning of the ozone

layer in the stratosphere – causing an increase in UV radiation reaching the Earth’s surface. In 1987 an international agreement, the Montreal Protocol, was signed, designed to protect the ozone layer by phasing out the production of ozone-depleting substances. As a result of this international agreement, the ozone hole is slowly recovering. It is believed that ozone layer will return to 1980 levels between 2050 and 2070.

In 1962 Rachel Carson, in her book Silent Spring, drew attention to the widespread and destructive ecological impact of DDT and other pesticides. DDT belongs to a family of synthetic compounds known as polychlorinated persistent hydrocarbons, or POPs, that are used as pesticides as well as in certain technological processes. POPs have been found to accumulate in the internal organs of living creatures and are believed to be responsible for increasing and widespread infertility in wild animals, and possibly also in humans. They may also contribute to an increase in breast cancer and reduced sperm counts in men. POPs are very persistent in the natural environment, and they have been found in the organs of animals in areas as far away from where they were released as the Arctic and Antarctic.

Three to four million tonnes of heavy metals, solvents, toxic sludge and other waste is `dumped into the world’s rivers and oceans every year.

Urban air pollution, due mainly to the combustion of fossil fuels, is a significant cause of ill health and death in many cities worldwide, especially in Asia. It is estimated that 2.5 billion people are exposed to air pollution levels seven times WHO guidelines.

Weaponry

The Anthropocene has seen an astronomical increase in the destructive power of explosive weapons. The nuclear bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki were many million times more powerful than the ‘conventional’ bombs of World War 1, which were themselves a product of the Anthropocene. Thermonuclear bombs now in existence are several thousand times more powerful than the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombs. There are many thousands of these bombs stockpiled across the world.

The two nuclear bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945 killed 129,000 to 226,000 people. The thermonuclear bombs stored in the arsenals of nations across the world are sufficient to wipe out humankind many times over.

Extinctions

The history of life has been marked by a number of mass extinctions, the most severe of which occurred around 250 million years ago when around 95per cent of all marine species and 70per cent of land species were wiped out.

A mass extinction occurred about 65 million years ago. Many forms of life disappeared, including all the dinosaurs and flying reptiles. Some groups of reptiles survived, including the snakes, lizards, crocodiles and turtles. Some birds and mammals also survived.

It is believed that 99 per cent of all species that have existed on Earth are now extinct.

As a result of human activities the present rate of extinction of animal and plant species has been estimated to be 100 to 1,000 times higher than the background extinction rate, and it is predicted that 50 per cent of Earth’s higher lifeforms will be extinct by 2100.

Food production

The UN’s’ Food and Agricultural Organisation warns that the world’s agricultural systems face the risk of progressive breakdown of their productive capacity due to excessive population pressure and unsatisfactory farming practices.

Fairness

Unlike the situation for the first 300,000 years of human history, gross disparities exist in human health and wellbeing across and within human populations.

CONCLUSION

This story of life on Earth reminds us that we humans are both a product and a part of nature, and that we are totally dependent on the processes of life, for our survival and wellbeing.

It also leads us to the inescapable conclusion that present pattern of human activities on Earth is not sustainable ecologically. Business as usual will lead to the collapse of civilisation. The days of ecological Phase 4 are numbered.

[1] Note: For my own short version of the Bionarrative, see S. Boyden. 2016. The Bionarrative: the story of life and hope for the future. ANU Press. Canberra. https://press.anu.edu.au/publications/Bionarrative.